This summer I took a research trip out to a charnel house.

The plan is this: by checking out peculiarly medieval Christian institutions – monasteries, painted churches, anchoress’ cells, shrines – I can maybe get a physical sense of how a world with an overwhelmingly universal and permeating hardcore Christianity would feel. Then I can try to reproduce it in the book for the planned extensions.

Plus, you know, it was summer and a jolly out is a jolly out:

So I jumped in the car and drove out to St. Leonard’s Church, Hythe in Kent. Because that is where there is a particularly good example of a charnel house:

A charnel house (or to use its less evocative name, “ossuary”) is a place where you store disarticulated bones that turn up in a graveyard while you’re either

- digging other graves

- extending church buildings and know you’ll disturb human remains (which is what is thought to have happened at St Leonards)

- deconsecrating ground that has people buried in it.

These remains need to be stored on holy ground, but you’ve no way of knowing who they belong to or where they should go by the time they’re dug up. You could rebury them, but odds are good in a crowded graveyard that there simply isn’t room.

This is a common problem. It’s worth remembering that in most ancient graveyards, the graves and monuments you can see represent just a tiny fraction of the people buried there. For instance, I did a little research survey on St. Mary the Virgin in Prestwich. The graveyard had been in continuous use for about a thousand years*. It was the chief church of larger parish, and huge numbers of people were being reported in the register of deaths every year. Yet until the earliest tombstone (dated 1643), not a single one of these was accounted for in the surviving grave monuments. That’s thousands of people we’re talking about, gone without even a marker.

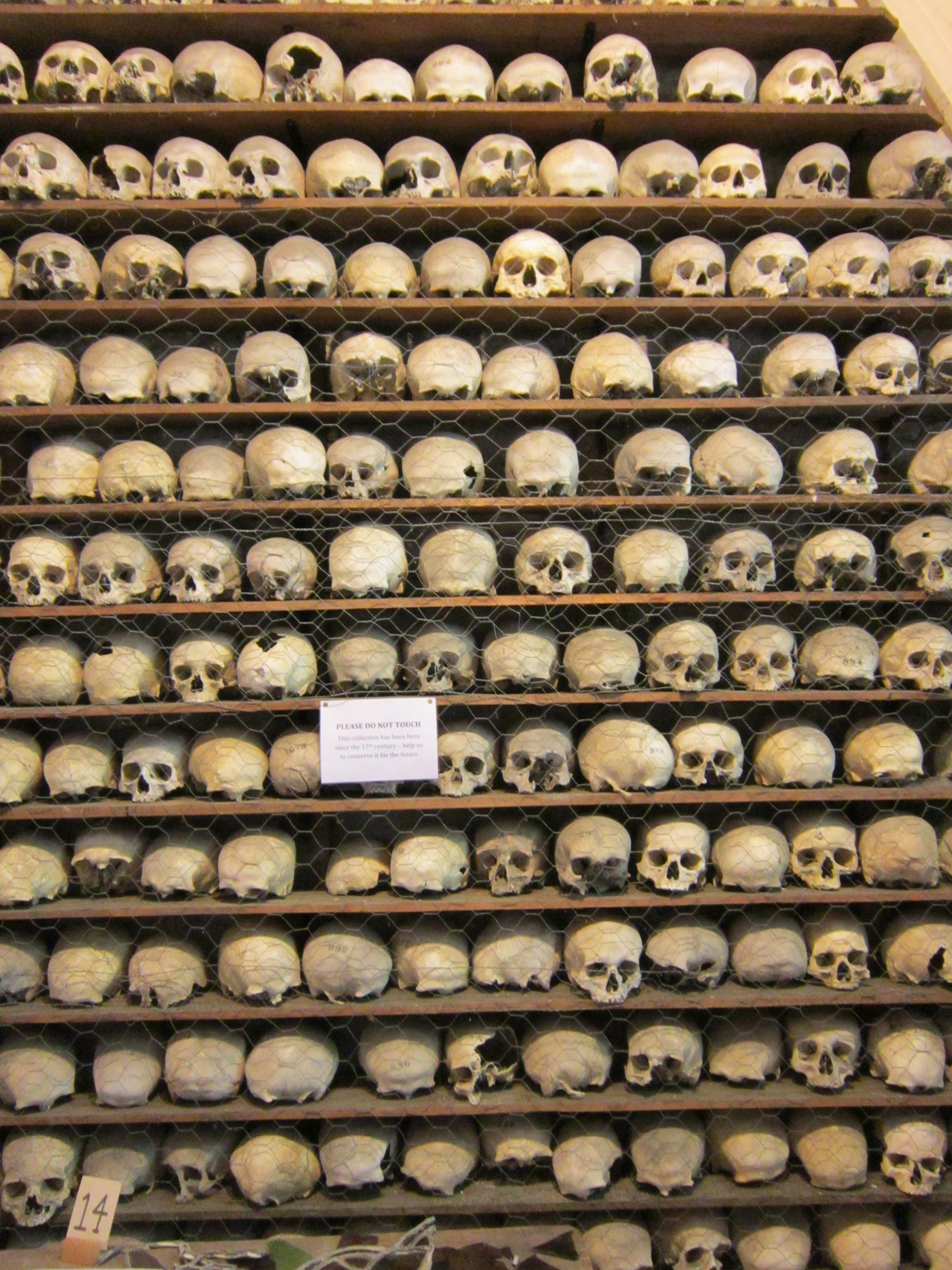

The Charnel House at St Leonard’s is home to over 2000 skulls and 8000 long bones, mostly thighs:

Not sure what I expected when I went in. Darkness, perhaps, or a kind of musty smell, fetid rags and strings of decaying flesh, you know – the usual.

Instead the whole room gave off this light, almost airy feel. The bones were clean and white, and uncoupled from their individual owners and piled in neat nubbly stacks against the walls, they looked not so much human but more like some very avant garde wall decoration. It’s not until you see the skulls that it hits you:

The bones are not only fascinating and somewhat moving in their own right, but they are also a library of how people lived back then. Some of the more interesting bones (and in one case, hair buried with the owner) are picked out in display cases:

The bones below show healed fractures, and the one riddled with holes represents a nasty case of osteomyelitis. This is an infection of the bone – those holes would have been filled with pus and bacteria when its owner was alive:

So recently I was having a conversation with someone about bones, bodies, and cremation – in particular ashes. More specifically, about the long, ritualised conversion of something that is unclean, liminal, and taboo into something that is handle-able, if you like, and thus within the pale (here is a very interesting video of the modern version of the process). I felt this very strongly in the charnel house, where the disarticulated bones, sorted by type, suggested not so much hundreds of dead individuals as much as a dead crowd. Their bones are not so much intrinsically part of them but rather furniture, or grave goods.

They had been reduced to signs of themselves, if you like, rather than their essence.

All said, it was very interesting, and I’d definitely recommend a visit. Hythe itself is quite charming on a beautiful summer’s day, and the volunteers working on the door were super-helpful.

CURRENTLY READING: For Honour and Fame: Chivalry in England 1066 – 1500 by Nigel Saul

*Archaeology Geek Footnote: Possibly far, far longer. I met a man, an amateur archaeologist who’d done a bit of digging and found some ditch and bank remains, who maintained that St Mary’s was potentially a rare Northern example of a causewayed enclosure. In addition to the earthworks, the fact that the original churchyard site was circular until relatively recently was also extremely telling. It’s a fantastic idea.