So, this weekend I did something a little different. I’ve been thinking ahead to my future projects. I wondered which crime project will follow Bethan Avery, the first draft of which is nearly complete. With this in mind, on Saturday I went out to Orford Ness.

Orford Ness is a nature reserve and historical site you can only access by boat from Orford Quay. It comprises of two parts; one of which is ancient artificial freshwater marshes that have cultivated since the eleventh century. Giant dykes separate these from the sea. The dykes have ridges of vegetated shingle on the North Sea side. Both sides are fragile habitats and almost completely barred to human beings apart from very set, narrow signposted routes. They host a lot of rare birds and wildlife.

Which is cool and all, but not why I went:

You keep to the paths here. Not just to protect the habitat, but despite the best efforts of the Bomb Disposal Squad stationed here, to avoid stepping on any live ordnance they might have missed and blowing yourself up:

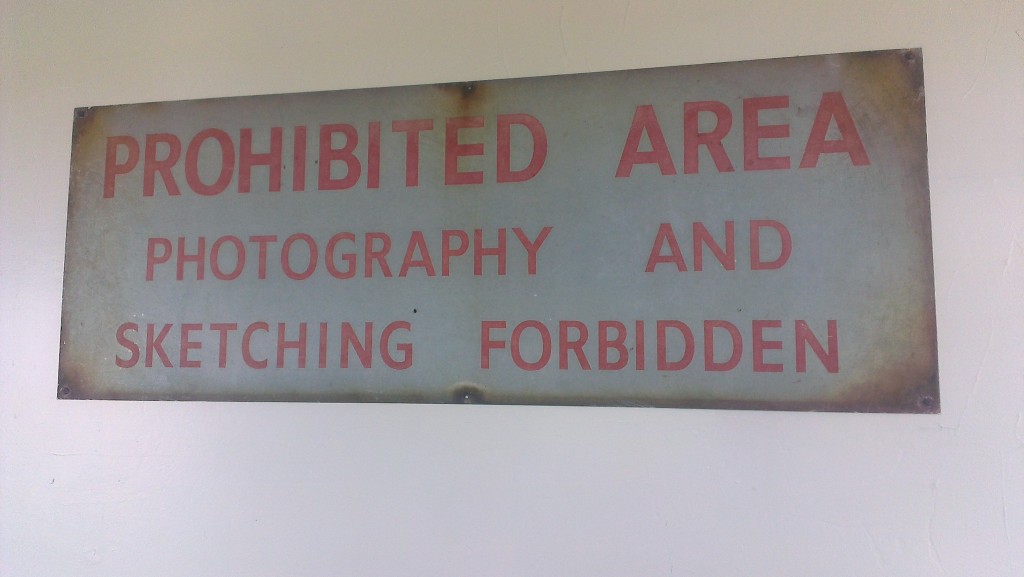

The military have owned the island, or strictly speaking the peninsula, for seventy years. From 1913 through to 1993, in fact, before the National Trust bought it from them. Throughout this period the activity on Orford Ness has been of a Top Secret experimental character. Parachutes were tested here, and it was an important site in the discovery of radar. They lined up planes and shot to pieces in lethality and vulnerability testing to find out what kind of punishment they could take.

But the most interesting thing on the island, at least to my mind, is the way it teems with Cold War military archaeology. In particular, the abandoned Cobra Mist complex, and the ruins of the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment site:

The main business of the Orford Ness site was not to test the nuclear warheads themselves. Rather, it was to test their explosive firing and triggering mechanisms. If you think about it, there is huge mileage in making absolutely sure that a nuclear bomb doesn’t go off in mid-air before you get it to wherever you, ahem, hope to apply it.

Equally, when you do apply it, you need to be sure that it will go off on impact, ideally when it hits the ground and not before.

The AWRE buildings take two main forms – the early labs, with their thick walls and thin aluminium roofs, now decayed away to skeletons:

They’re built that way to absorb the shock in case of catastrophic explosion. The shape funnels the blast upwards, towards the aluminium roof which would just be blown off.

Inside, the bomb is placed in an underground chamber. Here, air conditioning, vibrators, etc are applied to test how stable the device is in response to vibrations, temperature variation, G forces, etc.

The later, more imposing form the labs take are the “pagodas” which you can see from miles away. This is fortunate, because if you’re not on one of the Trust’s special guided tours you can’t get near them:

The spaces between the pillars were lined with thick Perspex (apparently glass proved to be a very bad idea).

In addition, you can see the remains of the “Hard Target” – a reinforced concrete wall mounted with cine cameras. Bombs were fired at this in order to test their impact capability:

A rocket-fuelled sled powered the warheads into the wall to mimic the correct impact conditions.

All of these ruined concrete structures lie surrounded by swathes of shingle. Vegetated or not, it does not inspire one with visions of rampant plant fertility:

The only life is inside the labs, where weeds run rampant inside the experimental cells:

You couldn’t wish for a more post-apocalyptic landscape in many ways. It is a science fiction landscape, like the triggering scene from some fictional dystopia.

And this is where the intrigue lies, because of course this is a scene from a dystopia – the one we all lived through while the Cold War raged. It’s a world you look back on when you reach the minimum safe distance and realise, wow, how profoundly screwed up all that was. Remember when we all thought we were going to perish in nuclear armageddon? Remember Protect and Survive and Greenham Common and When The Wind Blows?

It’s strange to consider now, but really, that world is only a few political accidents away again. Things once learned cannot be unlearned. And perhaps it’s worth considering that we may well be living out another dystopia now, one we cannot yet understand completely, because we’re not far enough away from its blast radius.